|

|

|

|

|

Essays On Art |

|

Edward Espey and Grafton Tyler Brown |

| It all started with a call I received from a church in Los Angeles in early 2007, indicating they had a small group of paintings by Edward Espey (1860-1889) they wished to sell. The paintings had been donated to the church by a couple of brothers who in turn had inherited them from their mother. The church had contacted me because of Edward Espey being listed on my website art wanted list. Works by Espey are exceedingly rare given that he lived a scant 29 years. Prior to this call I had only known of four Espey paintings in various collections, and based on the high quality of each of these works, I was extremely excited to have an opportunity to buy this group. Little did I know at the time that my acquisition of this collection of paintings would start me on a now 5 year saga of exciting discoveries relating to the Oregon art scene of the 1880s, especially regarding Espey and a fellow artist, Grafton Tyler Brown |

Dawn in Brittany

Dawn in Brittany

by Edward Espey |

Concarneau by

Edward Espey

|

|

|

...In my experience of being an art dealer focusing on historic Oregon art, it is my contention that Espey was the state’s finest artist of the 19th Century. He was blessed with the good fortune of having enormous talent coupled with having a father who attained success as a manufacturer in Portland who could afford to finance a first rate art education. In 1878 he left to study at the San Francisco School of Design, where he studied for at least two years. It’s not clear who his instructors were there, and a February 10, 1880 notice in The Oregonian notes that, “Ed. Espy, son of W. W. Espy, of Portland, is taking painting lessons here [San Francisco] from a noted artist.” Espey’s instructor(s) at that school may have included Virgil Williams and Raymond Yelland. By the summer of 1880, he was engaged in painting a large picture of Portland which he intended to exhibit in the Mechanics Fair. In June of 1882, a large painting by Espey entitled “Cascades of the Columbia” was purchased by a group of Portland businessmen and given as a gift to Henry Villard of New York, who had invested heavily in the transportation industries of Oregon in the late 1870s and in 1883 became the first benefactor of the University of Oregon. From 1882 to 1888, Espey spent most of his time in France. There he studied at the Academie Julian under Bouguereau and Constant. Like many art students in Paris during this time, Espey spent summers in Brittany and Normandy painting village scenes, landscapes and marines. He had accepted and exhibited 3 works on separate occasions at the Paris Salon, with his exhibition-sized work, Repose, winning a silver medal there in 1885. This particular work was purchased with subscription funds for $1000 by the Portland Central Library the following year where it remains on display to this day. Repose was the first significant public art work in Portland.

|

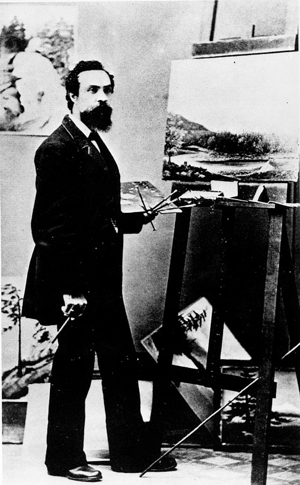

| ....Espey returned to Portland on various occasions and became a charter member of the Portland Art Club in late 1885. It was in this organization that Espey met Grafton Tyler Brown (1841-1918), another charter member. Born to a freed slave in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, Brown arrived in San Francisco in the early 1860s. His art career had followed a distinctly different trajectory than that of Espey and he is generally considered to be the first professional Black artist working in the West. His first notice in West Coast art circles was through his employment with San Francisco lithographers Kuchel and Dressel in 1861. The enterprising Brown purchased the firm in 1867, changing the name to G.T. Brown and Company. Brown sold the firm in 1879 in order to devote his time to traveling and painting. By 1882, he resided in British Columbia, eventually establishing a studio in Victoria, B.C. in 1883. At some point after this time, Brown ventured south to the Washington Territory, where he actively painted for the next 2 years. Prominent among his extant works during this time were various scenes of Mt. Rainier. By the end of 1885, Brown arrived in Portland where he promptly connected with other artists in the city, including Espey. |

|

Grafton Tyler Brown

Grafton Tyler Brown

|

|

| Brown actively exhibited with the Portland Art Club for the next 3 years, while Espey participated only to the extent that his time away in France allowed. That Brown and Espey became close friends may be ascertained by the fact that Brown was one of Espey’s pallbearers at his funeral in 1889. A promising art career was ended prematurely by the death of Espey at the age of 29 of Hodgkin’s lymphoma. His interment was at the Riveview Cemetery south of downtown Portland. Unfortunately, his grave marker bears a death date of April 1, not March 1, of 1889. By 1891, Brown had left Portland for Helena, Montana, and after a brief time there moved to St Paul, Minnesota, where he died in 1918. That Brown achieved a notable level of success in business as well as in his art endeavors may be attributed to him being able to “pass” as white, considering the level of racism evident in the West during the time. |

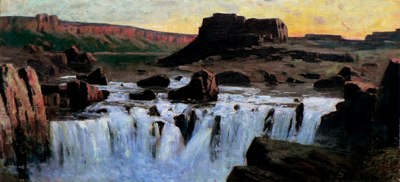

Shoshone Falls

by Edward Espey |

Grafton Tyler Brown,

dated 1882

|

....Having agreed upon a price and paying for the collection, I had to make a decision regarding how to ship the paintings back to Portland. I decided to drive down to Los Angeles and pick up the paintings myself in order to insure they were carefully handled and packed. When I arrived at the church, my contact there informed me that their records indicated there was one more painting in the collection they hadn’t mentioned to me, which they could not locate. The paintings were stowed away in storage areas of the church, and we eventually pulled out and identified those we had agreed upon. I asked for, and was granted, permission to dig around in some other storage areas in the church and eventually found a box with the missing painting. Interestingly, in the box with this painting, which was unsigned, were 5 lithographs by Grafton Tyler Brown along with one of the advertising brochures he developed that illustrated sketches of Yellowstone scenes. Prospective customers of Brown could identify a Yellowstone sketch they liked in the brochure, which Brown would develop into a painting. Judging by the large number of Yellowstone paintings by Brown that exist, it’s clear that this promotional brochure was a commercial success for the artist. |

|

....When I returned to Portland, I examined the paintings more closely. Eight of the thirteen paintings were signed by Espey, one was signed by a minor French artist, and the other four were unsigned. Of the signed Espey works, one was clearly a still life done as a student in Paris, two were American subjects, and the rest were works painted in France, in Normandy and Brittany. The largest was an 1888 marine with a sailboat on stormy seas measuring 40 by 60. The strongest work in my opinion was a view of Shoshone Falls in Idaho, painted at dawn. Two of the unsigned works seemed unfinished and I am currently unclear about their authorship. Two other unsigned works had handwritten inscriptions verso which offered the first clues that these were not by the hand of Edward Espey.

|

Grafton Tyler Brown,

Grafton Tyler Brown,

dated 1889 |

|

| ....One of these unsigned works was a fall landscape with purple hills, overcast skies, and colorful foliage, painted on thin cardstock and measuring 9 ½ inches tall by 14 inches wide. Written on back in pencil was the following: “View from the Eli Lequime store, R.C. Mission, Okanagan Lake, B.C, October 10, 1882.” Since Espey had sailed to France for study at the Academie Julian in June of that year, it became clear that he could not have been the artist of this particular work. Research regarding Brown indicated that in autumn of 1882, he had accompanied the Amos Bowman geological survey through British Columbia as expedition artist. I was able to acquire a facsimile of the unusually detailed exhibition brochure for Brown’s exhibition of 22 oil paintings in Victoria, B.C. at the New Colonist Buildings for one week commencing June 25, 1883. The brochure indicated that the paintings in the exhibit were studio paintings executed from oil sketches rendered on the Bowman survey. Each painting in this exhibit was described in copious detail. The first painting in the exhibition carried the title: “Long Lake, B.C., October 9, 1882, looking down the lake from the wagon road between Spallumcheen and Okanagan valleys.” The Eli Lequime store was a general store with lodging available on the second floor, located at the Roman Catholic Mission in the Okanagan valley at the southern end of Long Lake. Lequime (1811-1898) was an early settler to the area, whose son Bernard founded the city of Kelowna. Ostensibly, Brown painted this sketch from the front deck on the second floor of the Lequime hotel, one day after he painted the oil sketch of Long Lake. |

|

The second unsigned oil painting carried the inscription: “Indian Grave at Neah Bay near Tatoosh Island, Strait of Juan de Fuca, State of Washington.” The style of execution and palette of this painting, compared to the Eli Lequime painting is nearly identical. The composition consisted of a road that reaches a horizon line at the top of a hill. To the right of the road are a single tree and a large, monolithic rock formation, to the left, a thatched roof shelter for the Indian grave. The viewer looks directly north to see a cloudy sunset over the Strait of Juan de Fuca. In March of 1887, Brown exhibited a painting at the Portland Art Club: “Oil colors, sunset scene at Neah Bay, Cape Flattery. This artist has chosen a single rock to represent the subject, and has taken a time of day to get in as much color as the scene would admit of. The dark rock covered with rich autumnal tints of moss standing out in bold relief against a low toned sky with the last rays of a golden sunset seen in the extreme distance, gives a striking effect to the picture.” Whether or not the painting Brown showed at the Portland Art Club is the oil sketch described here is not clear, however, the essential compositional elements matched perfectly. What can be concluded with certainty is that Brown had visited Neah Bay. It is not clear if Brown added the inscription to this oil sketch at a later date or whether he returned to Neah Bay on another sketching trip, as indicated by the inscription which indicates that Washington had become a state. In any case, it would have been impossible for Espey to have painted the work, since he died in March of 1889 prior to Washington attaining statehood later that year. Further, there is no existing documentation of Espey having traveled to Neah Bay. |

| ....When it became increasingly clear that the two oil sketches described above were from the hand of GT Brown, I contacted a GT Brown scholar and curator. She expressed doubts that the works were in fact by Brown, based on notable differences in quality when compared to extant works by Brown. Most of the paintings by Brown that have surfaced have been larger works done in the studio which exhibit painstaking attention to detail. By comparison, these two sketches are notably looser, indicative of having been executed out-of-doors in plein air. To solidify my attribution to Brown, I hired a forensic document examiner who analyzed and compared the inscriptions on my paintings to inscriptions found on signed works and written documents by Brown. The results were conclusive, indicating that all the inscriptions were by the same hand, and therefore that the paintings could be attributed to Grafton Tyler Brown. |

|

At this point a number of other questions arose: Why were paintings by Brown and Espey comingled in a single estate collection? Whatwas the relationship between the estate and Brown and/or Espey? Startling information, as well as more questions, emerged as I continued to research the two artists and this collection of paintings..

Indian Grave, Neah Bay

Grafton Tyler Brown

|

|

| ....I decided to track both artists through the Portland City Directories. There I made an interesting discovery. Listed in the 1890 to 1891 Portland city directory was an entry for “Albertine Espey, dressmaker, (widow of Ed).” I had not previously known Espey was married, and so contacted the Oregon State Archives and acquired a copy of their marriage license. That document indicated that Edward Espey had married Bertine Legrandre (spelling not clear on marriage license) on January 19, 1889, just over a month before his death on March 1. Correspondence from an Espey descendant, Joyce E. Lytle, to Jack Cleaver of the Oregon Historical Society on February 2, 1981, revealed that Espey “…was married to Bertine LaJohn [sic.] Her father was a jeweler for Napoleon.” It seemed clear that Espey’s wife was a French national who came with him to Oregon on his last return from France. A curious issue regarding their marriage was the circumstances of the wedding: they were married in Benton County with only two witnesses (Espey’s father, W.W. Espey and Benton county pioneer, Bushrod W. Wilson.) The marriage was a simple civil ceremony which occurred on the same day they filled out the marriage license. No mention was made in the Portland newspapers, as if for some reason it was decided to keep the marriage a private affair. Espey had been suffering from Hodgkin’s disease, which would eventually claim his life. A visit to the Espey family gravesite indicated that a “baby William E Espey” who died on April 18, 1889 was buried there in an unmarked grave. I could not determine that this infant was the son of either of Espey’s two younger brothers. Was it possible Espey married Bertine because she was pregnant? More research will be needed on this front. |

| Another curious discovery I made in my research had to do with an interesting endnote I found in William Gerdts’ “Art Across America.” Espey is mentioned in his chapter on Oregon (in Volume 3) with a reference made to Espey works being exhibited in St Paul Minnesota in 1910. I requested a copy of the exhibit information from the Minnesota Historical Society and received page 287 of Kay Spangler’s “Survey of Serial Fine Art Exhibitions and Artists in Minnesota, 1900-1970, Volume 1” which informed me that 3 Espey paintings were exhibited in St Paul in 1910, over 20 years after Espey’s death. The lender to the exhibit was “Mrs. Espey Brown, St Paul, Minn.” When I first received this information, the thought had not occurred to me that Mrs. Espey Brown was in fact, the wife of Grafton Tyler Brown. A year later, when I obtained facsimiles of GT Brown’s handwritten wills (one in 1900 and the other from 1910) I saw that Brown’s wife’s name was “Albertine” and found that to be an interesting coincidence at the time. The only Portland city directory entry for Albertine Espey in Portland was in 1891, the year Brown left Portland for Helena, Montana. Apparently, Albertine left with him. After a brief time in Helena, the Browns moved to St. Paul, Minnesota, where they stayed until GT Brown’s death in 1918. As of this writing, I have not been able to discover what happened to Albertine after the death of her husband. |

Of particular interest to me regarding the 1910 St Paul exhibit was the title of one of the Espey paintings: “Sur La Route-Concarneau, Rainy Day.” In fact, one of the Espey paintings I acquired in the group had the identical title written on the back of the panel in French. It then began to dawn on me that the connecting thread between the Espey and Brown paintings I purchased as a group was Albertine. She would have inherited Espey’s personal collection upon his death, or at least, a part of it. She then would have comingled her collection with GT Brown’s after her marriage to him. Though it’s not clear what happened to Albertine or her collection of paintings after Brown’s death in 1918, it seems that somehow the group remained at least partially intact until 2001 when the entire group was donated to the church in Los Angeles. The brothers who donated the paintings to the church inherited them from their mother, Juliette Biscayart who was French and immigrated to the United States with her parents in the 1920s. How the paintings came to her is currently a mystery, though it’s possible there may be a familial relationship between Albertine and Juliette Biscayart. One can only speculate at what happened in the intervening 80 years between the death of GT Brown and the donation of the paintings to the church, but I hope to find out some day.

© Mark Humpal |

| |

|